Events in the Two Lives of an

Anti-Jewish Camel-Doctor.

by

PREFACE

This autobiographical effort is in two parts: the first deals with my experiences until I retired from the Veterinary Profession in 1928; the second, with events in the political pioneering career that I carried on after that year by opposing the secret Jewish Power. It was not until 1946 that I thought seriously of publishing it. On reading one of the numerous "smearing" articles about myself in the political columns of newspapers, I learned that my career, "told in full, would read like an Oppenheim thriller", and then it struck me that although there was much doubt as to whether it was as bad as all that, there were possibly some rather unusual events in it which might interest the small proportion of the public that reads.

For political reasons I have not mentioned in this book the names of most of my friends; and I hope my readers will not, therefore, attribute the fact that the word "I" too frequently occurs in the text to any want of modesty on my part; a man who has been in prison, with or without trial, for well over four years isn't likely to overestimate his own importance! I think that there will be many lovers of animals, veterinary surgeons amongst them, who may find something new to them, particularly in the first ten Chapters; whilst anyone concerned with political realism can learn a little from the experiences related in the second part of the book, since those experiences are rather unique. This, however, is neither a veterinary textbook nor a political treatise; it is simply an account of some of the things that happened to Your Humble Servant,

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

I thank the Editor of Country Life for permission to use three of my articles in that magazine, viz.:— Camels: Fiction and Fact; Mule Sense; and Toreador in Teesdale.

I thank the Editor of Wide World Magazine for permission to use my article Bill of the Desert; and for kindly supplying the block for the photograph reproduced on Plate III (1).

The Author.

CONTENTS.

Chapter I. The Root of the Trouble ... 1

II. A Slow Starter ... 3

III. Into the Hard Cold World ... 8

IV. Bill of the Desert ... 12

V. Six Years of

VI. On the Equator ... 22

VIII. Camels: Fiction and Fact ... 35

IX. Mule Sense ... 38

X. Private Practice ... 42

XI. Political Awakening ... 48

XII. The Jewish War ... 61

XIII. The Cold War after the Hot One ... 70

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

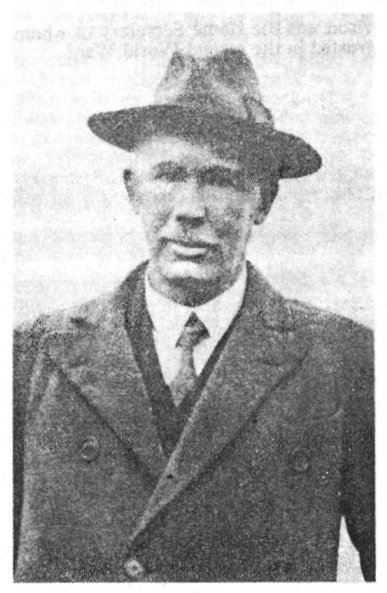

Page Frontispiece. The Author.

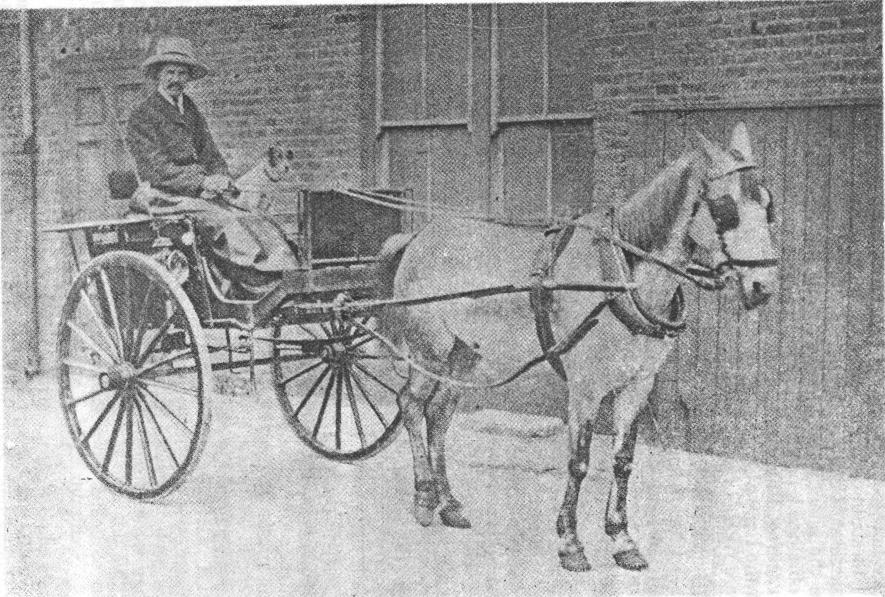

Plate II. West Ham to Chingford Express ... 10

III. (1)

Bill 12

(2)

Ata Mahomed, Bill, and friend 12

IV. (1) Vultures after a postmortem

... 17

(2) On the Bridge of the Ship of the

Desert ... ... 17

V. One of the first cures of Camel-Surra 20

VI. Author joins up in World War I ... 27

friend 45

(2) With Nandy

II ... ... 45

VIII. The late H. H. Beamish ... ... 69

NOTE,

A

number of the original photographs from

which the plates were taken, had faded.

The Author.

BORN 1878 — DIED 1956

OUT OF

STEP

CHAPTER I.

The Root of the Trouble.

Surely, everyone who attempts to write an autobiography should give his readers an adequate ancestral background against which to judge him.

Heredity always seemed to me to be a far more important factor in the basic character-formation of the individual than mere environment; it is one's forebears who hand down instinct, and what is instinct but hereditary memory born of fundamental experiences of past generations?

I have been able, thanks to the collaboration of many distant relations, to

trace my ancestry through many generations. But, of the Leese family itself, I

have no knowledge beyond that of a great-grandfather, Joseph Leese, of

The Leese family runs to a type which evidently has a strong prepotency: both sexes are generally tall, fair, blue-eyed, with heads broader than the typical Nordic average: any Mediterranean mixture by marriage soon seems to lose any trace; the general run of the family is of good intelligence with a strong sporting trend.

The Scurr family derived from one of William the

Conqueror's Knights who was given

1

RICHARD OASTLER (1789-1861), the Factory King, the man who did the pioneering and rough street work in stopping the atrocious conditions under which child labour was then employed in the northern mills, a cause in which the Parliamentary activity was done by the Earl of Shaftesbury; Oastler's political enemies silenced him for a time by foreclosing on him for debt, and he was imprisoned in the Fleet for over three years; then his friends bought him out, and his return to Bradford was in the van of a procession a mile long. After his death, a bronze statue was erected in that town, with the simple inscription "Oastler", in which he is portrayed with two ragged children at his feet. Oastler was the grandson of the brother of my great-great-grandfather, Robert Scurr. I hope I may be excused for boasting such a slender relationship to so grand a man. Mr. Cecil Driver wrote a very fine biography of Oastler, naming it Tory Radical (Oxford University Press, New York, 1946).

My mother was daughter of Charles Hudson, Coroner of Stockport, and of a

sound Unitarian stock of

My uncle, Joseph Leese, was made a Baronet, having been Recorder of

Manchester and Member of Parliament (Liberal) for

2

CHAPTER II.

A Slow Starter.

My father was an artist, but he had a modest independent income on which he

reared a large family. As a young man, he was of immense muscular strength and

I still possess copies of photographs of him "in the raw", the most

striking of which is a back view showing a physique of broad sloping shoulders

and narrow waist which reminds me of nothing so much as a section of the

Cantilever Bridge across the Firth of Forth. He could lift, with one hand, a dumb-bell

weighing 160 lbs. and raise it at arm's length above his head. I remember how,

when the family removed from

My mother was a very beautiful woman, a fact which I usually have to keep to myself, otherwise people are apt to crack the old joke, leaning forward, looking interestedly into my face to say: "Then it was your father who was not good-looking?" Her life was devoted entirely to the family and she taught us all to be civilised. Her eyes were blue and her hair was dark. I don't think any of us really knew what we owed to her until after she was dead. My parents lived in several places in the north, and before I was born there were already one son and five daughters. My eldest brother, Joe, was not a typical Leese; he was a strange mixture of scientist and musician and, as he was 13 years older than I was, we were never of much use to one another. Later in life, I found him so different in temperament and outlook to myself, that I decided the best policy to avoid a quarrel was to avoid him, which I did; and thank God, we never did quarrel. After him, every year or two

3

there came a sister, until five had appeared on the

scene. Being thus so close together in age, they tended not to look outside the

family for companionship and I believe they were very happy together. Then came

a gap of four years and, at Lytham, in

I was sent first to a dame school, where I kicked a girl on the ankle and

was "kept in" for an hour, bellowing the whole time: later to a boys'

day-school which bored me stiff. Finally, I was sent to

My mother had to do the best she could; I was, myself, very slow to mature. It was unusual for a lad not to know

the facts of life at the age of fifteen; I was a very innocent lad. Thinking it

all for the best, she had me articled to a chartered accountant where I spent

nearly three rather miserable years in the City. Then I woke up, decided that

the totting up of the profits of others was not for me and, with the help of my

dear old grandfather, overcame my mother's

doubts and went into the

4

altogether to be written off as a loss; at least I got a fine training in two things: firstly, in sticking out a monotonous job; secondly, rapid and accurate casting up of figures. Both these, especially the first, have been of great use to me in after-life. To think that I once passed the Intermediate Examination for Chartered Accountants with Honours!

Whilst I was at the accountants' office (Messrs. Craggs, Turketine & Co.), my mother and the rest of the family were without a permanent home and I went to live as paying guest with Mr. W. H. King, in Hampstead; he was an ex-Public Works engineer pensioned from India and he was a fine man for me to be with in those days. There I met my ultimate fate in his youngest daughter, May Winifred, but she was only 12 years' old then! I think the only exciting experience I had in the City was when I got inside the police cordon during the great fire at London Wall; but great fires in London have since become common-place.

About this time, I became aware of the fact that I had been suffering from

astigmatism (with short sight) for many years. It is impossible now to make any

estimate of the extent of this handicap; it meant that I had gone about without

seeing a number of things which were within the range of normal sight, but

beyond mine. However, I have much to thank my parents for in possessing a

healthy body and an active brain. I had grown up well fed and had never known

real hardship, and during my holidays had covered a large area of England and

Wales; but I still felt that I had been sheltered too much and that I knew my

country a great deal better than I knew my countrymen. However, from the time I

began to go out "to see practice" in my vacations at the

I had a younger brother, John Scurr Leese, born ten years later than myself with no other children in between, my parents having increased the population over a period covering twenty-five years! He, of course, was even more isolated from the others than I had been; he grew up a typical Leese, broke the high-jump

5

record at his school and vanished for ever at Krithia, Gallipoli, where he was serving in the first World War as a private in the 6th Manchesters. When I look back, I realise that I hardly knew him: circumstances and difference in age prevented it.

When I was a small boy I had made a bet with my sister, Nora, that I would

neither drink nor smoke until I was of age: on my 21st birthday I claimed the

sum and was duly paid. These so-called abstemious habits were retained

throughout my life; during adolescence 1 was free from a drain on scanty

pocket-money for one thing and I grew up with sound heart and lungs, and never

missed a single Rugby Football match when at the Veterinary College, always

being able to play as hard in the last five minutes as I did in the first.

During these early days, I was quite unconscious of any feeling that I was

missing anything by abstention; I abstained because I could not see why I

should drug myself just because other people did, and I did not make a virtue

of it; if I had, at any time of my life, seen any tangible advantage in mild

indulgence both in tobacco or alcoholic "refreshment", I would have resorted

to these things; but to this day I have never been able to discover that anyone

was ever a whit happier or better for them, and, to put it bluntly, I think

both habits are just "damned silly" where ordinary healthy men and

women are concerned. I don't think I could ever have really afforded them, as I

had to make my own way from the time I was able to write the letters M.R.C.V.S.

after my name. What I have often resented were gratuitous hints from the

drugged that I must not consider myself morally superior to them because I was

a non-smoker and an abstainer, because I never did, at least on that account! I

wasn't morally superior, at all; I was just undrugged.

I represented the normal; they represented the abnormal, and whose fault was

that? Surely, not mine? That is how it seemed to me. To them, I was abnormal

and they were normal! I think history records that

the subjects, but I think that the bovine complacency with which John Bull allowed himself to be reduced to a second-class Power by engaging in a wholly unnecessary war in 1939 is partly explicable by these drug habits, which I think are superlatively silly.

CHAPTER III.

Into the

Hard Cold World.

Although I had, during my college career, a large number of temporary spells

of "independence" when working with veterinary surgeons in the

vacations, the Summer of 1903 brought my diploma and full professional status,

and the first thing I did was to become an Assistant to a firm of Veterinary

Surgeons, Messrs. Batt & Sons, of Oxford Street,

London. In those days, there were few cars, and

The two assistants took on the night-work on alternate nights, and there was

plenty of it, too. Those were the days when people drove to theatres in

broughams and on cold nights horses would catch colds waiting for their owners

to emerge from places of entertainment. I had a telephone just over my bed, and seldom it was when it did not ring at least once on my duty nights. But I kept a spirit lamp and

kettle ready, and could always make myself tea whilst dressing to go out to a case. When the off-duty nights came,

I could leave work at

I often wonder how the modern veterinary student can ever

become a good horse clinician in the absence of the huge equine population that gave us of the old school such experience. A good equine practitioner was rather like a specialised Sherlock Holmes, who could take in all sorts of observations whilst hardly knowing he did it, and come swiftly to a correct diagnosis or prognosis. It was always the clinical work that interested me more than the scientific side; I liked to be with the animals and to study them so that no detail escaped me: veterinary patients seldom tell lies, but it takes close detective training to appreciate fully and quickly the meaning of their various signals of distress. I believe I was a good horse clinician; I was also strong on what I called "acrobatic surgery", which consisted of performing some slight surgical operation and springing out of reach before the animal had time to realise that anything had been done to him. I was only caught twice in my whole life: once when a horse kicked me just above the knee and once when a cow nearly tore my ear off with a hind foot. I always liked practice with dogs and cats, chiefly because I loved the animals themselves. Nowadays, a practice like Batt's then was, is simply unknown anywhere: so much have times changed!

After nearly a year of this, I was offered a much better job in the East End

of London, managing a practice for a deceased veterinary surgeon's executors in

West Ham, with a branch at Chingford, in

habit probably formed as the result of fright or ill-treatment when being broken in. Anyhow, tact eliminated it. The pony was so valuable in other ways that an occasional. new shaft was a detail: you could not tire her, even with thirty-five miles, and in Walthamstow and Leyton, when coming back from Chingford, we often overtook and passed the electric trams of that day, and we must have been a remarkable sight "going hell for leather", with the trap full of dog-patients for our infirmary at West Ham.

In the East End of London, the chief event of life in some classes of the inhabitants seemed, to use an Irishism, to be one's funeral. Big Flemish black horses were imported for use in these: they came in as three-year-olds and went straight to their work at that age; they could stand it, because, of course, they never really did any hard work at all. Sometimes I had to examine these new purchases as to soundness and the only way to test their wind was to drive them up a long hill in a hearse! These animals are very soft-hearted in sickness; the same remark applies to the popular Percheron horse; these continental horses definitely have a different sort of courage as compared with our native breeds. As an equine clinician. I found this interesting; I do not understand why it should be, but I know that when I am dealing with a Flemish horse or a Percheron, I can discount certain signals of distress which would be sinister signs in a Shire. For instance, after a bout of colic, the foreign horses will anticipate another attack by betraying certain symptoms of pain when no pain exists and no further attack is coming, moreover. The equine practitioner can always tell these cases by a brief examination of the pulse. The English horse goes back to the manger soon after the pain leaves him, nuzzling about for food.

In those days,

10

Plate II. West Ham to Chingford Express.

I then decided that the motor-car would oust the horse within my professional

life-time and that the prospects in horse-practice were not good enough for a

man who had a competence to make. I had about £400 saved and I determined to

take a post-graduate course at the

I had brought away from West Ham a bull-terrier pup named Bill; he was destined to be my closest companion for several strange years and deserves a chapter to himself.

11

CHAPTER IV.

Bill of the Desert.

Reprinted

from "The Wide Wide World", February

1949,

by kind permission.

Bill wouldn't have taken a prize at any serious dog-show. All the same, he could never have been mistaken for anything else but a bull-terrier. His mother was the most ferocious specimen of the breed that I have ever met with and was kept (usually on the chain) by a West Ham publican from whom Bill was purchased at two years' old for one pound sterling.

He grew into a formidable, but sweet-tempered dog, active and strong, with plenty of bone, well furnished with muscle. As from the first he lived with me day and night, he became—well, just what a dog of that sort naturally becomes to a man who had yet no other love.

The first year of his life was realty uneventful, except that when we moved

from West Ham to Vauxhall, he broke out next morning and disappeared. He came

back in the evening; but we found he had actually been as far as

After two months of Vauxhall, I went out East to investigate camel diseases

for the Indian Government and, of course, Bill came, too. We went out in the

hot weather, an unusual season in which to send newcomers out to

There followed a punishing train journey from

12

Plate III. (1) Bill

Plate III. (2) Ata Mahomed, Bill,

and friend

after the stifling days of dirty travel by rail and

road through the mid-summer hell of the Indian plains. The man did that all

right but left him in the sun and cold wind to dry. The result was that Bill

went down with rheumatic fever. I and a fellow-veterinary friend worked night

and day for ten days on a patient who could not move without a squeal of agony

and who could do nothing for himself. Somehow, we got him through, but it was a

very weak bull-terrier that went down to the plains with me and then back into

the hills to the Veterinary Research Laboratories, 7,500 feet up in the

Here I was calmly informed that dogs were not allowed it our living quarters to which I replied, with some heat, that I had not come from civilisation to mid-Asia to be separated from my dog, and the matter dropped.

Soon after, I got carte blanche to get on with my job, so down we went into the

plains, which we rarely left again. My work was field research in the most empty parts of North-West

Bill and I suffered about equally from the dry heat, but it was he who rushed out into the first downpour of the Monsoon racing and splashing through the puddles uttering squeaks of joy in the sensation of being cool at last.

Bill's travelling life was full of incident. One nuisance was experienced in the habits of pariah dogs. These ownerless curs, of all sizes, have regular beats like policemen in the villages they infest. No stranger dog can encroach upon another pariah's beat, which usually provides offal for the bare existence of one dog only. If a stranger dog is sighted, the pariahs of a village unite to liquidate him. Thus, when Bill, rolling along by the side of the baggage-camels, with tongue lolling, approached a village, one might see converging upon him a number of streaks of dust, indicating the rapid advent and onslaught of the pariahs of the place. Bill hardy ever started a fight, but was good at finishing one. Not for Bill the tactics of the pariah and the wolf—slash and break away! Singling out the most formidable opponent, he took hold and stayed where he held, using his weight as perhaps his mother had taught him.

13

His tactics defeated dogs twice his size, like the big Pathan sheep-dogs of the North-West Frontier. It was the foot of his opponent to which he attached himself as soon as he could. Then he would worry and pull away with his compact weight so that his antagonist could never close with him. It was wicked to see, but it is passing strange how he learned this trick; did he discover it by accident, or did he think it out? Occasionally, when he had a number of opponents, he got badly gashed, and I was always on my guard for the first signs of Rabies which happily never arrived.

Sometimes, when we crossed rivers, I would take Bill up on the saddle with me, but more often he swam them himself alter we had crossed.

Bill was a fearless, but tactful guard. The presence of Bill in my tent allowed me to sleep soundly in lonely places along the North-West Frontier which he and I travelled from Shabkadar to Dera Ghazi Khan.

Once he was lost in the desert. I had gone ahead on a riding-camel and

arrived at a well (our destination) several hours before the baggage-camels

with which were my servants in charge of Bill. My bearer, greatly agitated,

reported that Bill had disappeared ten miles back where there was thick scrub

in the desert: "chasing a pig," he said. It looked black for Bill.

Fortunately, I had a good map; after considering the position, I found there

were two other wells within twenty miles from the approximate place where Bill

had gone off. With a sinking heart, but somehow banking on the dog's

intelligence and instinct in making for water, I sent a camel-man to each of those

wells with instructions to wait all night and start back at

Bill's relations with camels were always friendly, though sometimes wanting in delicacy. On rare occasions, at the eastern end of our immense "beat", he met with elephants; unfamiliarity with these monsters made him aggressive and noisy, so, as he was quite without fear, it was considered a wise prophylactic measure to remove him as early as possible from their vicinity.

My bearer had a monkey; a quaint fellow who would jump from any reasonable height, say, the top of a bungalow, into my arms where he liked to sit, peering expectantly, from time to time, up my nostrils. Sometimes, after I had been cooling myself in the bath-tub, the monkey would take my place, swimming round and round under water and coming up occasionally to breathe. When

14

he came out, with his hair plastered down over his skull, he reminded me irresistably of a certain old acquaintance called—well, never mind! After the first tactful introduction, Bill accepted the monkey as "one of us"; he treated it as he would a human child, which he probably thought it was. He liked to feel the busy investigating fingers in his coat, and only mildly remonstrated when they pressed open his eyelids when he wanted to sleep.

In that half-wild life, even Bill's dinner wasn't always safe. Once he was discussing a bone in front of the tent, but had not observed the presence of two crows in a tree close by. One of these alighted a yard in front of Bill's nose, inviting inevitable attack, which Bill at once jumped forward to make, dropping his bone. In a flash, Crow No. 2 swooped on the bone, and the two cunning villains went off to share it together. One could not help admiring them for their sporting co-operation, so exquisitely timed.

Mahomedans are taught by their religion to regard dogs as unclean animals. However, my chief Veterinary Assistant, Ata Mahomed, a devout Mussalman and a kindly and observant lover of animals, saw something in Bill that wasn't written in the Koran. He loved him and would sometimes squat on the verandah with his arm round him, talking to him.

After about two years of this sort of life, I woke up one night with a

start, feeling something was wrong. It was. Bill was not on the bed. I lit the lantern and found

him under the bed, hardly conscious; he died five minutes later. I expect it

was valvular trouble, a legacy of the rheumatic

fever. He took a bit of me with him, I think. It was Ata Mahomed

who arranged his burial, and even photographed it for me to see afterwards; it

was Ata Mahomed who had a grave dug which was so

engineered with stones that the most clever jackal

could never penetrate it. There we left Bill of the Desert with a stone to mark

the place—"for ever

And I went on, alone.

15

CHAPTER V.

Six

Years of

My job was the investigation of camel diseases; it was unusual to send men out to India to arrive in the middle of the hottest season, and as soon as I reached Lahore in the Punjab, I was instructed to go up into the "hills" (the Himalayas) for two months, and spend my time learning Hindustani and also reading up anything that was known about camels and their principal plague, Surra or Trypanosomiasis. This I did and passed my Lower Standard language examination at the end of the time. I was destined for work far from the haunts of white men, and it would have been quite useless to go into the wilds with anything less than this very minimum qualification.

Then I was sent to Kathgodam, at the foot of the

hills below Naini Tal, to study Surra

which affected the

After a brief stay in the Muktesar Imperial Laboratory, magnificently situated 7,500 feet above sea-level right opposite the first great wall formed by the mass of the Himalayan mountains, I

16

Plate IV. (1) Vultures after a postmortem.

Plate IV. (2) On the Bridge of the

Ship

of the Desert.

OUT OF' STEP

left for the

I spent the cold weather getting all the experience I could with my strange new patients and decided that my most active days would have to be between the months of June and October, just when the plains were most unbearable; the reason was that Surra spreads only during that season in most parts of the Indian camel-country, although the sick animals may carry the disease from one season to the next, thus acting as reservoirs for the Tabanus to tap at the beginning of its season. This was not altogether a pleasant prospect, and was complicated by the fact that most camels go far into the desert at that season and are all the more difficult to get at. But my teeth were in the job, and I was immensely interested.

Postmortem work on camels which had died from unrecognised

causes was, of course, a fruitful source of information, but there were great

practical difficulties to be overcome, and sometimes when an outbreak of some

camel-disease had occurred, I would travel even hundreds of miles (by rail and

in the saddle) to arrive at the scene before the fierce sun had made conditions

impossible. Often, after we had finished an autopsy, we would look round to

find seemingly the whole population of North-West

It was often necessary to examine the blood of as many as a hundred camels at a sitting under the most appalling conditions; the blood was easily obtained by squeezing a drop out of a very slight nick in the ear of the animal on to a slide. The microscope had, sometimes, to be on the ground and I am surprised that no great injury appears to have resulted to my eyesight in this trying work in the blinding glare of an Indian sun.

17

OUT OF STEP

I soon took a dislike to the social conventions which ruled station life in

India, but as all my work was in the jungle and desert, I rarely stayed more

than a couple of nights in a city, staying just long enough to take in a fresh

stock of stores for another long trip in the "out back". Travelling was by horse or camel, and I soon reduced my

baggage to a minimum which surprised some of the other officers I met on tour.

I had two assistants, graduates of the

I arranged that the next Surra season should be spent in a known zone of the disease and that the principal work should be done with the use of ponies; ultimately the road from Saharanpur to Dehra Dun was chosen and I secured the use of a forest bungalow at Mohand, just where the highway entered the Siwalik hills. This place was known to be pretty certain death for tongs-ponies at that season. I arrived some time before the monsoon would bring out the flies, partly so that I could make a proper comparison between the fly conditions in the dry heat and those in the damp, but partly so that I could buy some ponies, build a stable and prepare mosquito nets on a large scale to protect certain of the ponies. We took several camels with us, which had chronic Surra; this to make sure that a source of infection would be present; and we had a number of white rats and white mice on which to investigate the various kinds of biting-flies' transmitting powers. As the place was very malarial, being surrounded by thick jungle full of all sorts of wild beasts, including elephant and tiger, I arranged a bamboo cubicle which, when covered with mosquito netting, enabled me to have my meals and evenings in peace. I did no shooting: I dislike killing animals except for food, and my business there was to do work. I used to keep fit by long walks with my bull-terrier companion.

18

OUT OF STEP

To cut a long story short, we proved that ponies protected through the whole Surra season by mosquito netting, yet otherwise in close contact with Surra-infected animals, remained free from the disease, whilst all the unprotected ponies contracted it. We also obtained a lot of information as to the relative capacity of the different genera of biting-flies to transmit Surra from one animal to another.

Armed with this definite knowledge, I returned to the

Everything pertaining to the proper management of the camel, his breeding

and feeding, down to the identity and seasonal value of the bushes he grazed

upon, was my business. In the first few Surra

seasons, I was travelling light through the monsoon

in the steaming plains when men who considered themselves luckier were

recuperating in the hills. I had to cover as much ground as possible so as to

detect the different areas which were reasonably safe from Tabanus

so that Camel Corps men could use them for grazing their animals in the Surra season. This work took me very far afield and there are few of the desert areas in

19

OUT OF STEP

centre and I had to live in tents until, at last,

they did. It was known at this time that certain arsenical drugs were capable

of banishing the trypanosomes from the blood of animals, although after a few

days' absence they would return: in some species of animal there had been

occasional cures. With such drugs as were then available, it was almost a case of

finding out how much and by what method the trypanosome could be finally killed

without damaging the animal patient. This monotonous work, however, was tackled

and in 1910, by a fairly long treatment, we had 50 per cent. cured by certain

treatments; similar results were being obtained in

Needless to say, when I became entitled to some leave, I was very ready for

it. By this time, I had decided that I would not stay in

20

Plate V. One of the first cures of Camel-Surra.

OUT OF STEP

great professional advantage; I left

The Indian Government had been ready to employ me in investigation work on

elephants, a job which I might have found attractive had I been fresh from some

temperate climate. But I felt that it would be difficult to become expert on

such a subject unless I could live on the job for at least three hundred years,

and as this wasn't likely, and I had no desire to leave a job on which I really

was expert to take on one at which I could not see how an ordinary lifetime

could provide enough experience to get one out of an amateur status, I decided

I would stick to camels. I foresaw intense interest in comparing the camel conditions

in other countries with those of

21

CHAPTER VI.

On the Equator.

When in

Before sailing, I visited the King family who were then at Southsea, and became engaged to my old friend, May Winifred

King; and it was intended that as soon as I had found my feet in

However, God disposes and things turned out differently. When I arrived at

Jubaland is truly Godforsaken, and the equator itself runs through it close to the mouth of the River. It is hot at all seasons and low-lying; it is malarial wherever desert conditions do not obtain. Most of it is desert, but the track to the north is never far from the river. It was no place for a white woman. Up-country life had to be lived in ramshackle wooden huts, and the only produce of the desert was livestock. On the other hand, there was game in plenty and on tour one shot one's own meat-supply. The menu

22

OUT OF STEP

could be dik-dik (a small

antelope about the size of a whippet), guineafowl, junglefowl, bustard, partridge, duck (where there were

lakes from the river-overflow in the rains), and sandgrouse,

which could be got at

The frontier was patrolled and guarded by the King's African Rifles, and

there was a mounted unit on camels about 100 strong, the men being Sudanese

chiefly, recruited from the defeated enemy at

The riverbank was infested with tse-tse flies for

a stretch of about 300 miles between Yonte and Selagli and all camel-transport had to be hurried through

this part of the route north, often doing 30 miles at night between 6 p.m. and

6 a.m. during which time the tse-tse is considerably

less active than in the morning after dawn or the evening before dark. The sun

rose at

I was never very happy during the 18 months I spent in this country; I had

not "clicked" with my superior, at

23

OUT OF STEP

camel had to take first place, and the necessary night-marching was very hard on the human element. I did so much turning night into day myself that when I left Jubaland, at the end of 1914, I slept very badly at night nearly all through the First World War. This work was preventive and not of enormous interest, but I derived a good deal of professional information from the many opportunities I had in comparing the conditions I observed with the Indian ones I had left behind.

On one occasion I was travelling up the right bank

of the

I spent several months at a forsaken spot called Serenli, 400 miles from the coast when you travelled on the river, and joined the expedition of Brigadier-General Hoskins when he went right on into the Marehan country to try and talk the natives there out of the necessity for a military expedition to make them behave. Whilst Hoskins did the talking, I was quietly surveying the routes for the future expedition if it were found unavoidable. Thus, the expedition could take place with the minimum camel-loss from Surra.

However, Hoskins made no great impression upon the Mare-

24

OUT OF STEP

han, and the expedition

was decided upon. I was sent right down to the coast where I had to arrange the

landing on an open beach, at Kismayu, of 350 camels

of an Indian Camel Corps which was to take part. The Commanding Officer, the

Native Officers and many of the men in this Camel Corps had known me well in

I had a row with the Government at this time, having received peremptory

orders from my Chief to join the expedition as Veterinary Officer. My status

being Civilian, with no provision for the possibility of my becoming a

casualty, nor any definition of my rank in a Military Expedition, nor any

certainty of my status as to discipline, I refused this order unless it was

first agreed on all sides that I was a civilian and nothing but a civilian and

would take no orders from anyone as to my work, but only as to my movements.

There was a lot of bobbery about this, but I got my

way; I was always anxious to accompany the expedition because of my friends

from

25

OUT OF STEP

at one camp, that from a pool in which a dead

ostrich had been lying. These things had told on my strength in such a climate

as Jubaland, and I became very feverish on the march

about 100 miles from the coast and had to be left behind; my face was so

swollen that my eyes were almost closed; I do not know what the condition was:

I had to be carried back to the coast on a stretcher by natives where, under an

Indian doctor, I made a slow, but complete, recovery. This was at a place

called Gobwen on the sandy banks of the

On landing at

26

Plate VI. Author joins up in World War I.

OUT OF STEP

removed from the tse-tse

country, where they really had no business to be. After two months' service in

the Serengetti "desert" (not really desert

as we camelmen knew deserts) I received instructions

to take the camels back to Jubaland. This I did,

returning on the same ship and demanding my release according to the agreement

made. After some humming and hawing, I received my discharge, and took the

first available ship, a French one, to

But the War Office, in

27

CHAPTER

The First Great Slaughter.

I was glad to get away from under the tropical sun; I felt that it had been affecting,

at last, my energy and initiative. I went to see my future wife and my mother;

and joined straight up in the Royal Army Veterinary Corps; I was rather

disappointed to be offered a mere Lieutenant's commission, but felt it was

hardly a time for holding out for terms! Anyhow, I was made Captain after nine

months' service. I was in

After a few weeks, we moved off, one night, down to the neighbourhood of Bethune, and the following day we heard that our last position had been laid flat by shelling. Here we stayed a long time; the batteries were, of course, up nearer the line; ammunition was very short at this time and our heavy horses were sometimes called upon, in pairs, to take up four rounds at a fast trot, which did them no good. At this place I remember seeing the

28

OUT OF STEP

(then) Prince of Wales marching with his regiment; and the Canadians would come down from the fighting line bringing their customary one white-faced prisoner to show where they had been. I had a lot of Units to vet at this time, and my professional rounds took me over a lot of ground. I spent Christmas Eve in the trenches with the Officers of one of our Batteries at Annequin and it was from an observer's post that I first saw the Germans with whom we were at war.

Veterinary work at the front in war-time is not very satisfying to the clinician, because prevention is his job, and he has to send all trouble to the rear to be dealt with by others. Detection of trouble at an early stage is the chief duty, but I used to treat some cases myself if I thought the delay in sending them back would prejudice their recovery.

Our Medical Officer at that time was a

After one year of service, I got leave and went home to be married. On my

return to

During my long stay in this Hospital, I was skilful enough to evade every Church Parade; there was always a sick horse to be attended to, just at the right moment! I always felt that Church

29

OUT OF STEP

Christianity was quite incredible; I am the son of a Unitarian mother and I believe that different races require different religions.

On one occasion Major Hobday, who was a high-grade

Freemason, announced that a Freemasonic meeting was going to take place in the

Unit and I realised that I was the only officer there

who was not a Freemason. Now although I was not a regular army man, I had been

long enough in contact with regulars in

Meanwhile, the British attack on

I was instructed to proceed to Hargeisa, not far from the Abyssinian border, and buy camels there. I had with me an Arab interpreter whose loyalty I had reason to doubt. At Hargeisa, I

30

OUT OF STEP

found that no camels were coming in for purchase,

so I called a meeting of akhils or headmen. Sitting

on a chair, I told these people to gather around in a semi-circle so that they

could hear the King's Message. I explained the need for camels in the war

against the Turks in

That ended the "ring". From that moment, I was able to buy an

average of 30 good camels a day for over three months; occasionally a feeble

attempt was made to form a fresh "ring" to send up the price, but I

broke these by saying I was well paid for my job and the longer they delayed me

in selling their camels, the longer I should be away from the carnage in

Europe. In the East, it is safe to appeal to the baser instincts of man. I

bought 3,500 animals at Hargeisa and Mandera, whilst the other three officers had collected

1,500 between them. Towards the end of the time, Major Herring-Cooper returned

to

By the time the last transport arrived to take us up the

31

OUT OF STEP

night. The instinct of mules in the direction of self-preservation is very strong: when suddenly dumped into deep water, they will try and climb upon anything that is afloat. There was not much afloat except men, so the mules tried to climb on them! My narrator said: "The night was dark and yet the water seemed to be all ears and teeth". A vivid description! Yet he went on, with tears in his eyes, "When a destroyer at last picked me up, one fellow rode up to the ladder on a swimming mule and when we moved off several mules were streaking after us trying to catch us up."

War is a beastly thing for animals as well as men.

When I felt like it, I reported my hitherto forgotten presence, and was told to join a transport for Marseilles, which I did, the only adventure on the journey being the appearance of a submarine, upon which our two escorting destroyers quickly enclosed us in a smoke-screen within which we changed our course and took temporary refuge in the bay where St. Paul was said to have been wrecked in Malta.

On returning to Abbeville, I applied for a spot of leave, but I was not one

of the General's "grey-haired boys" and was directed to take up

special duty at

One incident there might interest horsey men. My inspections of the horses, as they landed, was carried out

in the old moat around the ancient walls of

32

OUT OF STEP

were after him not to frighten or hustle him, and I got close to the spot where he would land, for he was looking down, snorting and fidgetting for a foot-hold. The height was about 25 feet, but the lauding was grassy and favourable. Then he jumped, and what interested me was to see quite plainly that although a horse taking an ordinary jump lands on his forelegs, this fellow, jumping from a great height, dropped his hind-quarters whilst in the air so that he landed on his hindfeet, thus breaking the shock. He was quite unhurt.

When this duty was done, I got leave and my wife and I went home together.

On my return to

The officers of the Unit itself were Royal Army Service Corps men, all selected for their jobs because of familiarity with horses, and they were very pleasant people for a veterinary surgeon to work with. On slack afternoons, which were rare, we would have an imaginary fox-hunt over the downs around Abbeville, with an imaginary fox and imaginary hounds. The purpose of the unit was to replace casualties from the front, our horses being conditioned, trained and paired as requisite, ready for supply.

33

OUT OF STEP

One day, a bright young red-hat from the Veterinary Staff came over to inspect my work. He asked me whether I saw to it that crushed oats were used so that the horses could get the most benefit from their corn. I said: "No, Sir" and he waxed eloquent on my oversight. When he had finished his tirade, I said, "Excuse me, Sir, but no horse leaves this depot unless he himself carries in his mouth the most efficient corn-crushing armament; trained men inspect every animal's grinders and if there is anything wrong with them, it is at once put right; further, if you will excuse me, Sir, these animals will not get crushed oats at the front and if they got used to eating them here, they would fall away quickly when they got up to the front where their work was hard and the corn fed whole." After that, I was left alone to do my job without interference.

There was a tense moment when the huge unit, which had been for years at

Abbeville, got orders to get ready to move to the coast at two hours' notice.

The Germans were in

34

Camels:

Fiction and Fact.

Reprinted from "Country Life",

permission of the proprietors.

Nearly every popular tradition about camels is without factual basis and how many fables there are concerning the strange specialised animal met, in this country, only in zoos and menageries! If it were not for our native mud, he might have been a familiar domesticated worker here, provided he received stabling in the winter and reasonable protection from flies in the Summer, but even then some tall stories might have survived, because there are people who still believe that the horses's eyes magnify what they see, and that that is the reason he submits to Man! The horse is protected from flies by a special muscle attached to the skin itself which shakes them off and by his naturally long tail. The camel has no such defences and soon becomes exhausted by the muscular effort needed to beat off swarms of flies. That is one reason why the camel lives in dry climates.

Man's chief interest in the camel is in the work he can do. The structure of the camel's foot is specialised for sand; it has a flat horny under-surface with an elastic spread, but offers no grip on a slippery medium like mud. If a loaded camel is taken carelessly over a patch of slimy ground, the legs are liable to slip apart, and he does "the splits"; he may, if lucky, get off with a bad sprain; if unlucky, he will dislocate a joint. So he is useless in a country like ours, although he could stand the cold well enough.

Exaggerated notions exist of the camel's capacity to resist thirst; it is great, but the camel, even if he doesn't look it, is, after all, flesh and blood. There are certain antelopes which exist throughout the year without access to spring or river water, but they don't have to do work under those conditions. The working camel always thrives best when he can drink as often as he wishes, but if the necessity arises, he can keep going and remain fit on intervals between drinks of two to five days, according to the breed of camel. He can endure and survive privation of water for a much longer period, but will then suffer and will need plenty of time for recuperation.

Perhaps the tallest of travellers' yarns about the camel is the

35

one which alleges that when lost in the desert and in danger of dying of thirst, a man may find relief by killing his camel and finding the bag of water which he is supposed to carry in his stomach. It would be much better to spend the time and energy in trying to find water somewhere else. There is no such supply maintained in the stomach; there is an excess of mucus in parts of the first stomach, but to suck some of that would act as an emetic and you would lose more water than you gained. The camel's specialised apparatus against thirst consists of an excess of mucus-secreting surface in the throat and in the first stomach, which enables him to moisten his food in chewing the cud, even if he hasn't had a drink for a week or so.

The camel's hump is a store of superfluous fat which is drawn upon when food

is scarce; it is relatively bigger and more efficient than the hump of the Zebu

ox, or the "spread" of a middle-aged man which may be a similar

provision of Nature so that he can tide over the longer intervals between

successful hunts as his activity declines; a pleasant thought, even if it may

not be accurate! The sheep in some countries similarly store fat in their tails

and I have seen a Doomba sheep, in

The camel's supercilious expression is accounted for by the Arabs who say that, while they know only 99 names of God, the camel knows the hundredth!

Sometimes it is stated that a camel-bite will give syphilis to man, but this

is untrue. The only disease which can be transmitted in this way is Rabies; a

keeper in

The dental armament of a male camel is terrific, because his four canine teeth are developed as fully as those of a lion, and he has been known to take the top of a man's head right off. The bite is always serious, and generally septic.

Camels are supposed to curl up and die out of sheer cussedness. Of this they are never guilty; they are full of a passive sort of pluck. The source of this tale lay in the unrecognised existence

36

of a widespread disease due to a trypanosoma which causes a very slow decline with a remittent fever, which many camelmen were unable to diagnose or understand. The camel "curled up and died" from it because of his refusal to give in to it before expending the last ounce of his strength. It is pleasant to record that a hundred per cent. cure of this disease can now be effected by a single injection into the jugular vein costing (before the war) about 3s. 6d.

Another yarn is that a camel cannot swim. He can, and does, although he is slow in the water. I have landed hundreds of camels on an open beach by having them lowered into the water in slings by a crane, releasing the slings and making the camels swim ashore. Camels are much heavier in front than they are behind, and so the hind-quarters ride near the surface of the water. Therefore, as they approach a shelving beach and get their forefeet once more on terra firma, they bob about in a most absurd fashion for many yards before they can resume their normal dignified gait, as they cannot at first get their hind feet down.

In the Delta country of the Indus, there are camels which graze in the mangrove swamps and live a most uncamel-like and amphibious existence, swimming from one part of their water-logged grazing-ground to another; fresh water has to be brought to them from up-stream in boats!

Then, it is said that camel-riding makes people sea-sick. At the walking pace, it might, but one does not use riding-camels at the walk. With horses, the best travelling is done by alternate walk and canter, except when they are "pacers" or "ramblers"; but riding-camels are used at the jog or amble, and are never walked except on steep slopes or slippery mud. With riding-camels, you plug along all the time, with halts at intervals. The camel has a wonderful arrangement of elastic ligament which takes a good deal of the strain away from the muscles at the normal paces.

It is rather a depressing thought that, although the camel is now understood so much better than he used to be, and his potential economic value is thereby enormously increased, the advantage has been cancelled out by the internal combustion engine almost as soon as the knowledge was acquired and spread. Whatever happens to camel-transport, there is some future for camel-breeders in the meat-trade, although few have recognised it yet. Camel meat from animals reared for food is excellent. A world scarcity of meat must favour the production of an animal which can fatten in country so arid that other animals would perish in it.

Perhaps the camel may, some day, exchange his present arduous life for one of pastoral ease. How thoroughly that ease has been earned!

37

Mule Sense.

Published

in "Country Life",

here by kind permission of the Editor.

Some people don't get on with mules, but I like them. It never seems, to me, fair to expect a mule to behave like a horse. Often you hear it said "I don't like cats", but behind this antipathy you will generally find that cats are expected to behave like dogs and because, being cats, they can't, they are often regarded as disappointing animals whose acquaintance it is hardly worth while to cultivate.

The fact is that mules have much in common with cats, far more than they have with horses, and infinitely more than cats have with dogs.

The mule gets his brains and his temperament from his father, who is an ass only in the zoological sense, being anything but stupid. It is not stupidity which causes the family donkey to need so much urging and encouragement on the outward journey when he is taking the children for a drive; nor is it stupidity that makes it almost impossible to train a mule to jump a hurdle when ridden. In both cases, the action which is being forced upon the animal is one which, he feels, profits him not at all., in the first case the donkey knows quite well that the stick will never be applied with enough vigour to hurt him in the second case, the folly of jumping a hurdle when you can go round it seems, from the mule's standpoint, so stupendous that it is worth any amount of thrashing rather than to submit to it. The attitude may be, in both cases, somewhat spoil-sport, but it is certainly not stupidity.

Mules, like cats, have a very fair share of brains, but they do not usually expend their talents with any generous object. By nature they are self-centred and cautious, anything but "sportsmen"; and if you want to see the better side of mule or cat, you have to work for it; the confidence of these animals can be won, particularly if the attempt is begun during colthood or kittenhood. Once your mule or cat associates your presence with complete safety, everything else is easy and you will find he has affection to spare. A dog gives his affection generously and a horse his services, often to unworthy masters, but a mule never. He must be sure that

38

he is in good hands and can only be persuaded of it by experience; once he becomes satisfied about it you can do anything with him that is reasonable, but nothing which seems stupid to him, like jumping hurdles.

Personally, I find it attractive to gain the affection and confidence of an animal which is naturally suspicious and cautious.

The genius of a mule or a cat, if genius it can be called, is spent upon the serious business of self-preservation, and the well-being of "Number One". But if the cat has nine lives, the mule must have at least ten.

Compare the behaviour of a tired mule with that of a weary horse when a return to the stable is made after a hard journey. As soon as the harness is off, the mule is lying down, sometimes even before there has been time to get a good bed of straw under him; a horse will fidget and wait until all the men have gone away and the stable is quiet before he, in his turn, will get down to it and take his rest.

And mules think. A mule once played a trick on me that in a life-time's experience with animals I have never once known a horse resort to. Liquid medicine had to be administered and the usual procedure was adopted of throwing a rope over a beam, making a fixed loop in the end of the rope, passing it under the noseband of the headcollar and then into the mouth, and then pulling on the rope until the mouth was raised a little above the level of the "swallow". The medicine was then carefully poured into the side of the mouth from a bottle. The only horses which cannot be "drenched" in this way are those which really fight. But this mule used his brains and did not get excited. He found the medicine not altogether pleasant to the palate and so, mule-like, distrusted heartily both it and everybody connected with it. He could not get his head down so as to let the stuff run out of his mouth. So he deliberately stood up on his hind legs like a circus-horse every time he received a mouthful, which position, of course, enabled him to get his throat at a higher level than his mouth, so that the stuff ran out on to the, floor. In the end he defeated us until we made a counter attack by giving him a "ball" (pill) instead.

The difference in temperament and outlook between horse and mule is well illustrated by their relative behaviour when being chloroformed for an operation. The chloroform is administered on a sponge inside a special cylindrical-shaped muzzle which covers nose and mouth, the animal of course having been thrown down with his legs tied. Horses always react the same way; mules also react the same way, but not like horses. The horse, as soon as he

39

smells the chloroform, loses his nerve and begins to struggle violently; the very struggling increases also the rate of breathing and so, of course, the rate at which he takes in the fumes; with the proper dose, he goes under, unconscious for any surgical operation, in ten minutes.

Not so our mule. He does not get excited at all. He seems to say to himself "Great Oats! What's this funny smell? I dislike it and think it evil. Darned if I will breathe it." So he stops breathing for as long a time as he can hold his breath. When he can stand it no longer, he gives a great gasp and stops again and so on. The result is that it takes much longer to get a mule "under" than it does a horse, and you have to use a bigger dose into the bargain.

During the latter part of the last War, I was Veterinary Officer to a big R.A.S.C. depot which had the job of replacing horses-casualties in transport units at the front. This work involved trying out strange horses so that they could be properly paired for issue. Of course, it was not uncommon for animals to run away on their trials. When that happened, word was sent to me and I would ride to the scene to do first-aid on any injured animals. With horses, it was usual to find the animals hurt more or less severely. But with runaway mules it was quite a different picture. The waggon might be in splinters; the driver might be badly injured or even killed, but invariably the mules would be found grazing peacefully by the side of the road without a mark on them. After a number of fruitless journeys after runaway mules, which did not provide me with work, I stopped going where mules were concerned. I concluded that when mules run away, it is not because they are frightened, but because they think it fun.

In the Army, in the last War, we had a number of totally blind horses and mules for which work was to be found at the bases. The blind horses, with absolute confidence in their drivers, thrived so well that you could recognise them at a distance because of their fatness. But it was asking too much of mule-nature to expect blind mules to be a success. They were not, because they would place no confidence in strange drivers or, indeed, anything but seeing for themselves; and as they could not see, they would not work.

It so happens that most mule breeding (by a jackass out of a mare) is

carried on in "Dago" countries where the treatment the animals get,

particularly in the process of breaking-in, is, to say the least, rough and

ready. This is enough to destroy the chance of getting the wary mule to put his

trust in

40

to be nervous of them; a mule standing in a stall has a big advantage over a man who approaches it from behind and a mule can "cow-kick" with a long reach forward and sideways as well as backwards. This very nervousness on the part of the soldier makes it more and more difficult for the mule, which senses it, to learn to rely upon his judgment. He remains a rebel, a kicker and a biter. Only by long service under a really animal-sensed and sympathetic man can mule-nature be overcome.

Even during the period of my own life-time, cats in this country have been more and more adopted as real pets instead of being regarded as mere mouse-catching chattels unworthy of much notice, especially by men. Already, as a result, they have a greatly diminished fear of strangers; they have become emancipated and being better understood; their suspicious, cautious outlook on life is becoming modified.

If the British Army bred and reared all its own mules, the animals would

soon lose the evil reputation that has been thrust upon them by men who did not

understand them; both mule or cat which has never known ill-treatment lives its

life believing in Man, using its mule- or cat-sense on the basis that

41

Private

Practice.

Being demobbed and intending to have a spell of

private practice, I had consulted with my fellow-officers in the Advanced Horse

Transport Depot, who had not, of course, lost touch with English life as I then

had, and learned of several districts where there seemed to be a good chance of

making a success of general practice. First I went up to enquire at Ulverston, on the Barrow peninsula of Lancashire, but I

turned the district down as everyone agreed that farming there was in a

backward state; but I met a retiring veterinary surgeon, who sold me many

useful instruments, cheaply, so I had not wasted my time. Then I went to

Kendal, but there were too many sheep and too many old-established practitioners

there for me, so I moved to the next place on my list, Pontefract.

One look at that was enough; and so to Doncaster.

Here again, although the district was developing rapidly, there were several

good practitioners who had been there for years, and I opined that there was no

great need for even such a genius as myself so, further south to Stamford, at

the extreme southern extremity of Lincolnshire. I spent several days in

inquiries and then wrote to my wife that we had found our stamping-ground. At

first we had to take lodgings and I put up my plate under that handicap. The

cautious people of

Meanwhile, I had visited

42

OUT OF STEP

In those post-war times, I was unable even to buy a man's bicycle; and my

first journeys as a veterinary practitioner in

When, at last, I secured my house in 20,

As soon as I saw the horse I wanted, I bought it; a roan mare which we called Methel after two friends of ours named Maud and Ethel: I looked after her myself, and I was never so fit as during the time when her early-morning toilet demanded my regular services. She became very fond of me and had her own gentle snickering language in which to tell me so. When I drove out with her, it was two pals going out into the world together. I bought a governess car at an almost prohibitive price, and with that we worked up the practice. She was never sick or sorry, and I had a system of stable management which fitted the irregular hours we had to keep.

We generally had at least one spare loose-box, and her "bedroom" was another. The first thing I did in the morning was to take her out of her bedroom into her "sitting-room" where her feed was awaiting her. There was no bedding in the sitting-room, and I groomed her there, leaving the mucking-out of the bedroom until such time as was convenient on any particular day. That reduced the unavoidable before-breakfast stable routine to a minimum. I developed a large canine and feline practice in addition to the ordinary horse and farm work and sometimes I would have as many as twenty dogs on the place and I was both vet. and kennelman and did all the work myself. There were three separate enclosures where dogs could exercise themselves and when there was a crowd of them, it took some scheming to reduce the time occupied in this process by exercising compatibles together. The dogs seemed to appreciate my hospital, as a rule, and often we opened

43

OUT OF STEP

our front door to find an ex-patient, recently

discharged, sitting on the doorstep. One old terrier of fifteen years walked in

twelve miles from his country home on several occasions, a testimonial which we

accepted with mixed feelings, because somehow, he had to be got home again. I

remember one tight-skinned fox-terrier which was a great favourite

with us, bursting in through a window curtain. He still remained a favourite! Our large house was able to supply us with spare

rooms for cat patients; these rooms were closed to all traffic, and the

chimneys had to be stuffed with bags of straw, because cats in a strange place

will stick at nothing to make an exit if they can. I considered it disgraceful

for a veterinary surgeon to allow any animal placed in his charge to take

French leave; all the time at

When I had had my mare, Methel, one year, I sold her to a farmer friend who, I knew, would use her right and I bought a Morris Cowley car. But what a price I had to pay, so soon after the war! But, once I had got used to the car, I found it fully justified by the time and trouble saved; one got to one's cases sooner, which is always an advantage, and night-work lost most of its terrors.

For years afterwards, my mare, if standing by the kerb, would be able to detect my footsteps even if I was walking in a crowded street, and turn her head and snicker in welcome. Finally, she was sold again, this time to a dairyman and she was still working his milk-float when she was thirty-three, always with a clean bill of health!

Then came the deflation of 1926 and the great strike; it was

44

OUT OF STEP

the farming industry that was hit most severely by the falling prices and my practice suffered a blow from which it never recovered. The farmers drew in their horns and kept less stock and that of less value. People began to get short of money and the tendency was to let sick animals rip until they were too far gone for successful treatment. Of course, in addition to this, horses were rapidly being replaced by mechanical traction; the long and short of it was that I began to have some spare time in my practice.

One thing that I did with this spare time was to write a textbook on the

camel in health and in disease; I had long intended to do it, indeed I

considered that the opportunities I had had in the past and the salary and

allowances I had drawn from my camel-work made this an obligation. When this

interesting job was done, I snatched time off to see a London printer of

veterinary works; but his ideas were fixed and could not be shifted; he wanted

to produce an imposing volume about 3½ inches thick which would cost a

purchaser 26/-. Now I hadn't been a camelman for

nothing, and I knew that every ounce of weight that could be saved in my

treatise would mean a few more sardines in the chop-box for someone! I said I

did not want my work to be in the form of a large tome, but a compact book in

rather small print. He just could not see it. So back to Stamford I went and

there I arranged with the printer of one of the local newspapers to print my

book, and I made my own arrangements about the illustrations for it; finally, I

got an account-book binder, in Kettering, to do the simple cover for the book,

and turned out the article I aimed at for a cost to purchaser of 16/-. I

expected to lose £100 on this venture, but actually, in time, I made a profit

of nearly that amount! The book is the accepted camel text-book, and I wrote

two supplements to it containing information which brings the book up-to-date.

The Governments of

In 1928, I retired from practice, having had nine years of it without a holiday; I handed it over to an ex-serviceman who had been under the weather. I am glad I retired when I did; and I do not think I should like the life a modern veterinary surgeon leads in the country, with so much stress placed upon rather uninteresting preventive work with cattle, involving frequent rectal examinations and with that dear creature, the horse, taking such an insignificant amount of his attention.

Before I leave

45

Plate

our magnificent friend.

Plate

OUT OF STEP

bitch which could not pup; after the removal of a dead puppy and the birth of several live ones, the bitch was found too weak to rear all the litter, and yet the owner wanted to save the pups. I bethought myself of Binkle, the aforesaid cat. So I said: "Let me take a long chance and see if our cat can help". I took the superfluous pups home, got Binkle out of earshot, removed the litter of kittens and destroyed them, and put the pups in the place where the kittens had been. Then we brought Binkle back and stood by ready for action, for normally she hated dogs. As she stepped into the cupboard, she stopped as though she had seen a ghost, and her tail became twice its proper size. For a tense half-minute, she remained thus, then climbed in among the pups and there was no more trouble; but she never licked them and at first was frankly puzzled by the noises they made. She brought them up, small as she was, although one was taken from her at the fourth week because it was clearly beyond her strength to continue to suckle the lot; this pup was taken back to its legitimate mother, who, after being prevented from killing it, suckled it until weaning time.

Two of our cats mastered the art of opening latched doors; for this reason we had to use a hook and staple to prevent the larder door being at their service. They would spring up and hang on to the handle of the door with one paw and pull the latch down with the other paw; and if there were two working together, the other cat would shove the door at the right time. How they ever learned this trick, I cannot tell. It may sound incredible, but I once saw Nandy, our yellow cat, sitting on the back-door mat with his mother and the latter got up and evidently wanted to go into the house, the back door being shut; Nandy got up, opened the door for his mother in the way I have described and then went back and sat down on the mat again. I record this, not as a case of chivalry or filial sense in cats, but as a remarkable bit of co-operation.

Animals like that, I always feel, are not so far removed from us. I always regarded Christianity as a religion alien to white men's instincts, because it takes no note of man's best friends who share his hearth. It is in the East where dogs are pariahs. I think it a pity that Christianity has not been adjusted better to the spiritual needs of Nordic men, who do not need to be told not to murder and steal; a white man's religion would begin on a higher plane and teach him to be straight-forward, to be kind to animals, to be courageous, loyal and chivalrous.

One of my patients had been a St. Bernard dog, born in

46

OUT OF STEP

have him?" As this great dog was 10½ stone in

weight and as high as a table, I felt it incumbent upon me to consult the

mistress of my house before coming to any decision; but she knew the dog and

said "Yes" at once. So Barry came to us, although we always called

him Knob, because he had one on his head (anatomists call it the "occipital

tuberosity"). It was always more like having a

guest in the house rather than a dog, except when we had to follow him around

with a "gob-cloth" to wipe away the slobber which he could not help

depositing in places where no slobber should be. He was our magnificent friend

for some years and went with us to

CHAPTER XI.

Political Awakening.

The deflation of 1926, which was the real cause of the general strike, had

hit every business in the town of

One thing had been worrying me for some time. I could not understand how it was that, although we had won the war, we seemed to be losing every yard of the peace which followed. Something, I felt, must be acting like a spanner in the works.

Then I heard the late Mr. Arthur Kitson speak at

one or two political meetings of various complexions. Kitson

had worked about 35 years for Monetary Reform, a subject of which I knew

nothing; he owned a factory in

48

OUT OF STEP

came to understand that here was something affecting the lives of men, women and children everywhere, and which existed as an unrecognised evil manipulated in secret by a few people greedy for Power. In fact, I saw that control of the issue of Money was Power.

Apart altogether from Kitson's influence, I had watched with interest the bloodless revolution of Mussolini, who by sheer determination had ended the chaos into which Liberalism (disguised) had brought his country; it appeared to me that here was a movement which might end political humbug, and his declaration "My Aim is Reality" appealed to me strongly. I wrote a little pamphlet Fascism for Old England, suggesting that only those should have a vote who were willing to pay for the privilege; every man would pay a sum equal to, say, one day's income, according to his means, before he would receive the suffrage; it seemed to me good realism that what a man had to pay for, he would value and that the electors would become a body of people who would vote for the country instead of for their own selfish interests. I also joined an organisation called the British Fascists, and I made a special journey to town to implore them to change their name, as I thought the initials were just asking for it! To my surprise, I failed to gain this obvious reform! After a while, I found that there was no Fascism, as I understood it, in the organisation which was merely Conservatism with Knobs On; it was justified by the Red attempts to smash up meetings of the Right, but it should never have been misnamed. Failing to get anything altered, I left the "B.F."

I have often heard people say that you cannot define Fascism; I always said

I could: a revolt against democracy and a return to statesmanship. In 1924,

there had been a General Election a few days before the local Borough Council

elections took place. The Conservatives had announced their intention of

"fighting socialism". When the Borough election approached, we found

that quite contrary to this declaration, Socialist Councillors

were going to be allowed to return without a fight; so my friend, Harry

Simpson, and I put ourselves forward as Fascist candidates. Every effort was

made by the local Freemasons to dissuade us, and we were told that no fresh

blood ever got on to the Borough Council in Stamford at the first attempt; but

we put in a lot of hard and sickening work canvassing our wards and the result

was we both got in, beating the two principal camouflaged Bolsheviks, pillars

of their Party, to the astonishment of the town. I was a Councillor,

of course, for three years, but found it dull work. Simpson served his three

years and then put up again as Fascist and was re‑elected; I did not try

again as I knew I was leaving the town. We were the first constitutionally

elected Fascists in

When canvassing for this election, it was impressed upon me

49

OUT OF STEP

what utter humbug the democratic vote really is; many people, I knew, voted for me because I had cured their pigs or pets and without the slightest idea what I stood for, beyond that. (Talking of pigs, I went once to see an Irishman's pig which had developed ugly blotches on its skin; I found on examining the animal, that these were bruises, not disease, and traced them to mischievous stoning by small boys. The Irishman remarked "I don't like cruelty to animals, especially dumb animals!" What is it that makes the Irish say these funny things? I have never heard the answer to this question.)

I had about 80 so‑called Fascists organised in the town, but very few of these meant business. I often ask myself what was the bravest act I ever did? Well, it was to turn out into the streets of a town (in which everyone knew me) in the black shirt uniform. I had never done any public speaking before and almost literally shook with nerves at first when going through the soap‑box stage; but I stuck at it until I had no nerves at all.

When I retired from professional work and left the town, I started with four

others to found the Imperial Fascist League in

Arthur Kitson had introduced me to the Jewish

Menace, of which hitherto I had no real knowledge. (I was 45 before I knew

anything about what was going on behind the political scenery). He was very

nervous of the Jews because of threats and injuries received, and would never

speak of them at his meetings, but he knew all about them. He introduced me to

a little Society called "The Britons", in

I have been conducting a research on the Jew Menace ever

50

OUT OF STEP

since, and I wish here to emphasise that I have done it in the same scientific spirit as when I was investigating camel diseases in the world's deserts. I have been after truth, not propaganda; in fact, I investigated the diseases of the body politic!

My hands were full; research required time and concentration; running an organisation also required time and was apt to interfere

with concentration. Progress was painfully slow, because although I myself

could produce the means to prevent collapse, I could get no funds to splash

about for publicity. However, after about a year, we were able to move to

bigger offices, first at 16,

51

OUT OF STEP

we should hate to drive a motor‑car with 56 gears in it, and that the only part of a motor‑car which we could think of to compare it with was the back‑fire from the exhaust!